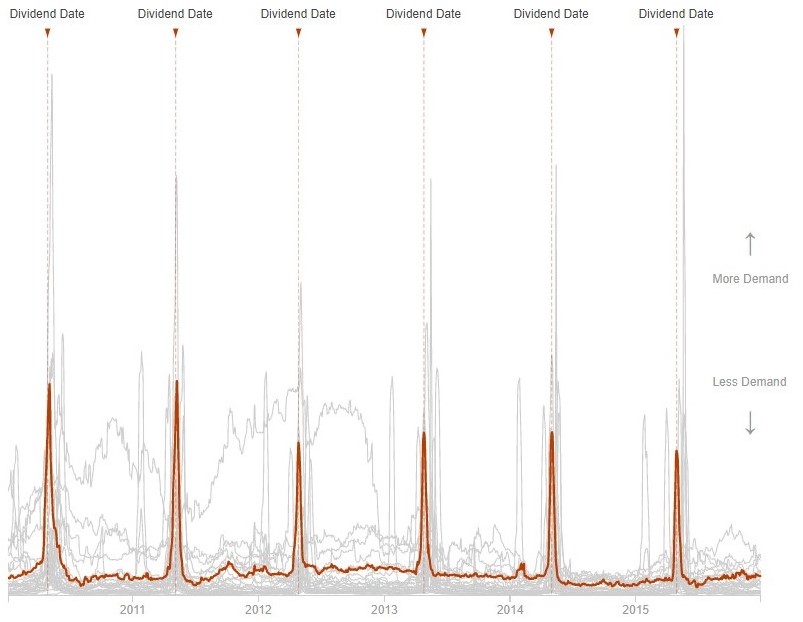

So here’s a riddle. Most of the time, there’s pretty tepid demand to borrow shares of German companies – except once a year, when they pay shareholders their a big annual dividend. That’s when demand to borrow shares suddenly – but briefly – surges.

If you were to plot shares on loan for any one of these high-dividend German stocks, you’d likely see a heartbeat-like pattern like the one below for chemical maker BASF. Why is that?

In the spring of 2016, I set out to find the answer with the help of a collaborative team of reporters in Germany and the U.S. The answer, we found, was tax avoidance. We ended up captioning the above chart “tax avoidance has a heartbeat” which pretty much sums it all up.

For years, big U.S. banks had arranged deals for international investors to briefly lend their shares to German funds that don’t have to pay a dividend tax on their stock holdings. The avoided tax – usually 15 percent of the dividend – was split by the investors and other participants in the deal. Everyone won except German taxpayers, who lost at least $1 billion a year on the deals, according to our data analysis.

Similar deals extended beyond Germany, siphoning revenue from at least 20 other countries across four continents, according to a trove of transaction logs, emails, marketing materials, chat messages and other communications among deal participants that we reviewed as part of our investigation. Commerzbank, the troubled bank lender rescued by German taxpayers during the 2008 financial crisis, emerged as one of the big facilitators of such deals, known in the industry as “cum/cum” stock loans.

The investigation was an unforgettable collaborative effort that I led with reporters from German broadcaster ARD, the Handelsblatt newspaper in Düsseldorf, and The Washington Post’s legendary business columnist, Allan Sloan. With Allan’s expert eye, my data crunching and our German colleagues’ local knowledge and expertise, we quickly made sense of the documents and figured out how it all worked. Special thanks to Allan and ARD’s Pia Dangelmayer and Wolfgang Kerler, among many others, for a collaborative effort that I’ll never forget.

Our joint reports published in May 2016. A page-one expose in Handelsblatt landed our story in front of Germany’s readers, and ProPublica and The Washington Post co-published our reports online and in print. ARD produced an in-depth video report on their investigative program, report München, which brought together all of our reporting into an eight-minute TV segment. You can watch the full segment below.

Impact from our investigation was swift. Germany’s then-finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, immediately criticized the stock-lending deals as “illegitimate.” Within days, the Frankfurt general prosecutor’s office opened an investigation into Commerzbank for its role in the deals. Most importantly, in June 2016, about a month after our report, German’s lawmakers voted to end the trading strategy. They enacted legislation that made it uneconomical to execute the tax avoidance schemes.

I also teamed up with Børsen, Denmark’s top business and financial newspaper, to dive deeper into the impact of these trades on Danish taxpayers (a page from Børsen’s report is pictured above) . It turned out that Denmark was a big victim of these trades: For a country of roughly 5.7 million people, the lost revenue equaled about $10 per resident, according to our calculations. Børsen ran a front-page expose of our report, which also prompted swift political action.

Why does this all matter? As my colleague Allan pointed out in a subsequent column, a schlupfloch here, a schlupfloch there and soon we’re talking about real money. “Schlupfloch” is the German word for loophole. And if there’s one thing Wall Street is great at, it’s exploiting loopholes.

That’s where incentives come in. The story of these dividend tax avoidance trades is a classic example of how well-paid bankers, lawyers, investors and accountants will eagerly look the other way and sign off on questionable deals if they’re incentivized to do so (and if the likelihood of getting caught or called out for it seems minimal).

The flip side of that story is integrity. There are good people in every industry who want to do the right thing and who have courage to speak up when they see something they know is wrong. It is through them, and the risks they endured, that these important stories came to light.

At the end of the day, the “cum/cum” trades we exposed were just one piece of a much broader dividend tax avoidance strategy that the New York Times called “the biggest tax heist ever.” I talk about them here in the past tense because authorities have taken action to close the various schlupflochs in the U.S. and E.U. But if they’re coming back – or if you have documents or data that could shed light on who was involved and help hold them accountable – we should talk. Here’s how to contact me securely.