In late 2021, as I was finishing a feature about how cybercriminals exploit corporate data leaks to target people with scams, I learned of a new fraud tactic in Southeast Asia that was quickly spreading around the world. It was a uniquely successful type of scam that routinely robbed people of their life savings. And it was being perpetrated in part thanks to a new form of modern-day slavery in which people are tricked into working as online scammers inside nondescript buildings scattered across Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and elsewhere. The term “cyber-slavery” quickly came to mind.

I immediately pitched the story to my editors at ProPublica, and in Sept. 2022 we published my report on this troubling new phenomenon, “Human Trafficking’s Newest Abuse: Forcing Victims Into Cyberscamming.” The dual narrative tracked the story of a young Chinese man tricked into working inside a criminal operation in Cambodia, where he was forced to lure foreigners into online investment scams, along with a Chinese-American man who ultimately lost his life savings to one such scam as he contended with the death of his father.

To construct this dual narrative, I interviewed dozens of scam victims around the world and people who had been trafficked into these cybercriminal operations. In the process of doing so, I learned the inner workings of these scam mills and the toll they exact on victims on both sides of the world: Droves of young people from China, Malaysia, Thailand, India and other countries who get trafficked into these scam operations in Southeast Asia, and foreigners in over 40 countries who have reported falling victim to the fraud perpetrated by these cybercriminal groups. Telling their stories called for insightful and compassionate storytelling, and I’m grateful for their time and the trust they placed in me.

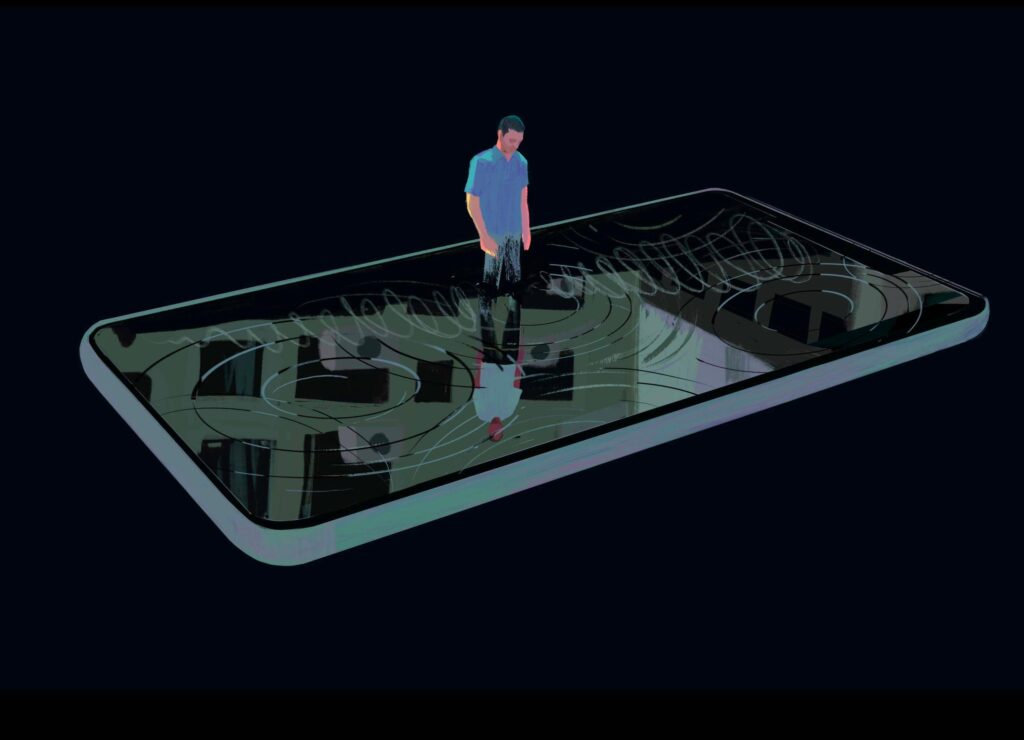

I followed-up with a report exposing the “pig-butchering scam” tactics that are commonly employed by the cybercriminal operations perpetrating these cyber-frauds. The term, 杀猪盘 or “shā zhū pán” in Chinese, is an allusion to the practice of fattening up a hog before slaughtering it. Once human-trafficking victims strike-up a chat with a potential target, more experienced members of the criminal syndicates take over the conversation. They then try to build trust and convince the target to deposit more and more money into fake online brokerages which, unbeknownst to them, steal all their money. Once the targets become unwilling or unable to deposit more money, the websites and the scammers disappear without a trace – until a new website pops up targeting new victims with the same scam under a different URL.

The Cambodian government moved to shut down some of these scam compounds in September 2022, but the problem hasn’t gone away. If anything, it has only gotten worse as more scam syndicates have shifted operations to lawless border regions between Thailand and Myanmar, where many cybercriminal groups continue to operate with impunity. Smuggling networks now operate in over 20 countries, luring human trafficking victims from as far away as Africa and South America to scamming operations that are now pivoting to new AI tools and techniques to target people. The growing crisis prompted Interpol to issue a global warning in June 2023, calling scam-linked human trafficking a crime trend that is “escalating rapidly, taking on a new global dimension” and “likely much more entrenched than previously thought.” Jürgen Stock, Interpol Secretary General, said at the time that “what began as a regional crime threat has become a global human trafficking crisis.”

All of this means that my work isn’t done. I’d like to do more reporting on this problem. If you have a newstip or story to share, please get in touch. Here’s how to contact me securely.